16 March 2022, the international news is reporting about a visit of the heads of the governments of the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovenia to the Ukrainian government. Three weeks into a war of aggression against the Ukraine, prepared in a way meeting the immense security challenges, the highest officials of these governments traveled to Kyiv by train, meeting President Selenskyj of Ukraine. Amongst other, the delegation included Vice President Jaroslaw Kaczynski of Poland. Vice President Kaczynski went public following the meeting by demanding an armed “NATO Peace Operation”, acting with approval by the Ukrainian President, on Ukrainian territory. That request is generating a flurry of public comments, covering the full spectrum of why this would be very complicated, or unlikely, or way too early.

Time to have a select look on the state of peace operations, why current operations struggle, leading to some thoughts on basic preconditions for peace operations, ensuring the unfolding of civilian aid and assistance.

To start with a term the United Nations got used to: “Robust Peacekeeping” was coined some years ago within the United Nations. It was used even by highest officials to describe the environment in which Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) of the UN increasingly found themselves: Being tasked with peacekeeping where there is little or no peace to keep. There is a notion of exasperation and despair in this term which I so vividly remember from many speeches. In the doctrinal framework of the UN, “peacekeeping” sets in after a peace settlement has been achieved, or, after at least some ceasefire agreement has begun to take shape. PKO such as MINUSMA in Mali, or MINUSCA in the Central African Republic provide the painful experiences which forced peacekeepers to adapt to situations where their real raison d’etre was a lofty dream. Never before the UN lost so many lifes, and the UN tried to adapt by making PKO more robust. So, that’s how the term “Robust Peacekeeping” was born. Member States of the UN and the UN Secretariat even accepted a path of providing the PKO MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo with a specially equipped and trained military intervention brigade authorised to “neutralize” elements. A term used for describing offensive lethal operations, not limited to the objective of defending the PKO and its mandate. Much has been written about this extraordinary step going beyond the concept of armed military or police mission elements for self-defence and defense of the mandate in a UN PKO.

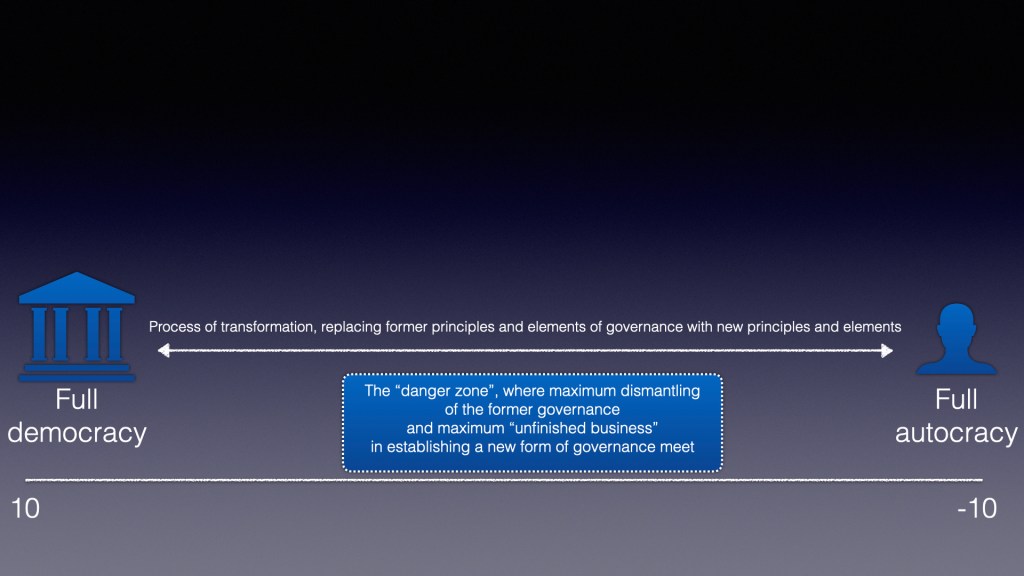

There always were some blurry lines between how the UN uses the term “peacekeeping”, NATO is using the term “peace support operation” (PSO), or, in a similar way, how the African Union (AU) describes their own engagement in Somalia through AMISOM. Yet, in broad strokes, there is a distinction between “peacekeeping”, “peace support”, and “peace enforcement”. The UN limits itself to “peacekeeping”, current missions of the European Union in the field of civilian and military crisis management follow that line, NATO has experience in “peace support” and certainly in “peace enforcement”, the AU in “peacekeeping” and “peace support”. All these missions broadly are “peace operations”.

Of course and by contrast, any use of the term “peacekeeping” by the Russian Federation in relation to the horrible invasion of, and war in, the Ukraine by Russia is not only misleading propaganda, but a blatant abuse of the term “peacekeeping”. Taken together with the use of the term “special military operation” it is trying to evade the accusation of a violation of the Charta of the UN: That Russia is waging war against another sovereign State, a Member State of the United Nations. In order to get a common position allowing 141 Member States to condemn, only 35 Member States to abstent, and just Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Russia and Syria to vote against, the Resolution had to speak of “military operations”. We often hear the phrase “being on the right side” today. On that right side, this military operation is a war. It is ongoing, and it is escalating, and there is no current publicly visible sign hinting towards a path of peace negotiations. Even talks about humanitarian corridors for evacuation of civilian populations utterly fail.

The fact that Russia appears, in addition to violating Art. 2 of the UN Charter, to commit war crimes against the civilian population in the Ukraine, stands separate. 16 March 2022, U.S. President Biden took the unprecendented step calling President Putin of Russia a “war criminal”. Taken the violation of the UN Charter and the alleged committment of acts constituting war crimes together, this is making the use of the term “peacekeeping” by the Russian Federation an insult to anyone who has worn a light blue UN beret, a dark blue EU beret, or the green beret of the African Union.

Vice President Kaczynski’s suggestion to establish a NATO peace operation needs to be specified in terms of what this would mean, and it never is too early to think about what comes ahead. In whichever way the catastrophe strangling the Ukrainians will unfold further, we shall never give up efforts and hope that this can be stopped. From what I understand from the public comments of Vice President Kaczynski, a “peace operation” would require a peace agreement, or a ceasefire declaration, meaning it is not “peace enforcement”. More likely, it would be understood as something resembling “robust peacekeeping”. Then, Russia, and [the Ukraine] would have to agree how to move forward on the incredibly winded road restoring peace & security. Note the square brackets: The Russian President decided to recognize the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics declarations of independence just hours before starting his military operations, or, in my view, war. Which led to widespread international condemnation, in return. How a Peace Agreement, or the rationale for a ceasefire declaration would play out will be incredibly difficult, and any international mediation will be a nightmare. But nothing is more important in order to define a difference between a peace operation having a chance of supporting return to peace, and a peace operation where there is no peace to keep. It is the single defining difference for the immense suffering of human beings in the Ukraine.

Many also push against the idea of a NATO peace operation, for the obvious reasons which brought Vladimir Putin to the point of attacking the Ukraine, and demanding its demilitarisation. On top of it, he wants to decapitate the Ukrainian government, claiming a “denazification”. But that is another horrible story, another lie. Here the question would be, in case of any chance for a peace agreement or ceasefire declaration whatsoever, who the implementing organisation or entity would be that could be tasked with a peace operation. From what I have read, Vice President Kaczynski is rather pragmatic: It can be NATO, it can be others. So it can be the UN, the EU, OSCE, NATO, or any combination of those. All of those have done peace operations, in the form of peacekeeping operations of the UN, crisis management operations of the EU, peace support operations of NATO, peace enforcement operations of NATO, or OSCE missions.

As mentioned, it never is too early to begin thinking about what comes after. Too often the results from planning are less than optimal otherwise. Mistakes haunting the international community for years have been made right in the beginning, during the conceptualisation and design phase, and reasons do not only include unalterable facts of the political environment for these planners, but also severe shortcuts because of time constraints. The earlier the thought process and the better the results, the less suffering for people after this war is stopped.

It is suggested that this operation is including at least armed elements, provided with a possible mandate of armed self-defense. Nothing more specific, so far. Also not about which civilian tasks would require armed protection. The request for armed means especially makes a case for a mandate by the UN Security Council (UNSC), since obviously a sole request from the Ukraine would not suffice in the given dispute, and also specifically in light of a historical dispute on interventions, where there was no such mandate by the UNSC. Assuming no veto by any of the five permanent members, the implementation by any suitable international organisation would be possible.

Without a UNSC Resolution, any operation would not survive the first day of our coining it a “peace operation”. It would be treated as a military aggression, escalating the existing conflict, perhaps in dramatic ways. However, it is important to be clear that nothing like that could hope to fly under the brand name of “peace operation”.

Final thoughts on mandate elements of a “peace operation”: Little to nothing has been thought about in the public which elements such an operation would have (military, police, civilian). Nothing is clear in relation to that armed capability, how robust, for which purpose, and whether it will entail military elements only, or also police elements, and whether they would be robustly equipped too, and for which purpose.

On earlier occasions, this blog contains many articles which point towards the vast experience available in the field of international policing and its cooperation with military elements, both in the UN and the EU (including the External Action Service itself, but also specific initiatives started by groupings of EU Member States, such as the European Gendarmerie Force EGF and the Center of Excellence for Stability Police CoESPU). There also is institutional knowledge about these topics within the NATO Center of Excellence for Stability Police.