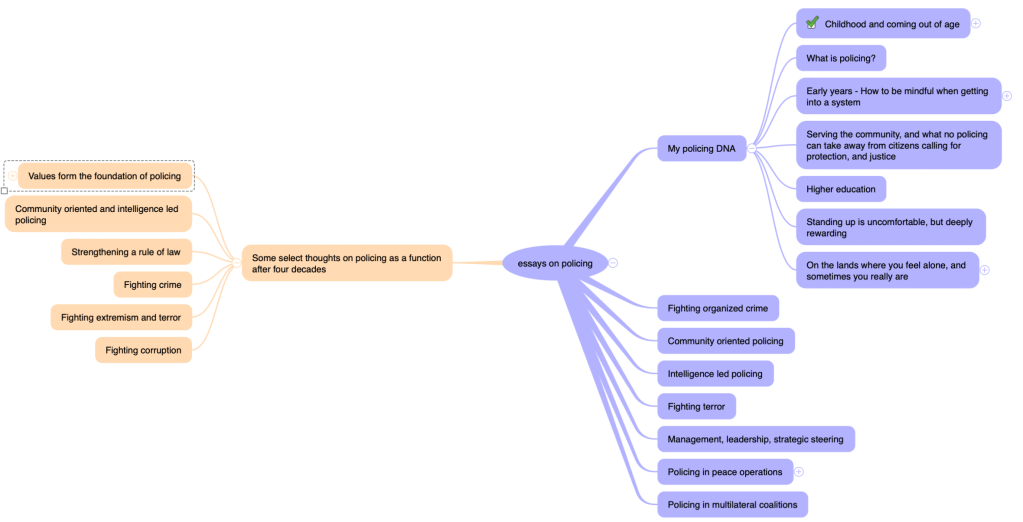

How to navigate within these essays: Initially these essays were meant to form a book. I have decided to publish them, step by step, on this blog. By nature of blogging, the most recent article appears on top of all other articles, whether they are part of this anthology, or they address other issues. If you want to read these essays like a book, HEAD OVER HERE and navigate through the content of the entire set of essays on policing.

On the featured picture: Being a young detective police officer – There was nothing resembling any computer in my office. We used typewriters. Landline telephones. Radio communication. The only computer connection was in an office in headquarters which had connections to State and Federal databases through a terminal. You would call that office by phone, or by radio. As a backup for this computer connection we had a thick book containing basic data about all persons with an active arrest warrant. Just in case the computer system would not work. If I needed to look into more information about a person of interest, or into fingerprint registries, or information to items like, a stolen car or a seized weapon, I had to get into the car and to travel roughly an hour and to walk into registries and archives in headquarters. Those were the seventies of the last century.

2022 I was stopped with my van during a routine traffic checkpoint in Bosnia&Hercegovina. The officer took my license card and radioed from his car to his cantonal police station. There they were checking manually if I would have any outstanding traffic citation in that canton. It took a few minutes, then I was allowed to continue with my travels.

I grew up with being told that the most noble way of learning is from following wisdom advice given to me, and that the hardest way to learn is from making mistakes. In a way, this established a pattern of attempting to avoid mistakes, and to feel ashamed when I made some. It took me a very long time until I was able to embrace the simple fact that life is about experimenting, that life is about learning from consequences of one’s own actions, and that a robust framework of advice and accountability would allow me to navigate in a positive way, embracing the aftermath of situations when I had to correct my course, to hold myself accountable, but not to beat myself up about it. Like, with my own children today: I may provide them with reference points which allow them to circumnavigate some challenges in their lifes, where I hope they may do better than I did. But I will not be able to prevent them from making own, sometimes very painful, experiences with consequences of their own actions.

This sets the stage for my reflections on what the term “integrity” meant in my upbringing as a police officer, and what it meant as I rose through the national parts of my career. Later, in my international career, I would be confronted with efforts to establish, or re-establish policing in a society. I always struggled with attitudes to to this quickly, to “stand up a force”, and to expect that this would work without a long-term approach which provided the opportunities at the root of a system to ensure integrity by putting these efforts into the core of education, and management.

In order to make this thought practical, I will reflect on my own upbringing, as this is the only and the most crucial reference point I have. The reader may relate, or have other experiences, and thoughts. These here are mine. I believe that, within efforts of international assistance to peace&security by institution-building, there is a more or less binary decision to make: Either to accept the long-term approach, and to commit sustainably to it, or to not add assistance to institution-building into the overall concept of assistance. Like, say, in the case of Afghanistan, where part of the reason why our assistance efforts faltered may sit with the incoherence of strategic plans, and to find a genuine way into domestic ownership. There are many other reasons, of course. But to see a billions-of-dollar-exercise with uncounted numbers of international experts involved in building policing in Afghanistan disappear in an implosion, is sobering. To say the least. For many of us it is disappointing. I belong to those who feel sadness and shame.

So, how did I find my own way into the police, and policing?

A child’s view on police, and what they do

What are my first memories?

Like many children, I loved that time of the year when you can don a costume. In Germany, this is what happens during the “carnival season” around February. Children, but also adults, will slip into another role, dressing up for it. In North America children have a similar habit on occasion of Halloween, October 31st,.

Kids don all sorts of phantasy costumes on those occasions. I remember that, more than fifty-five years ago, I always chose being a “cowboy”. It didn’t require much else than a cowboy style hat, perhaps a vest made from some plastic resembling leather, and putting on an artificial mustache, even drawing one with some eyeliner was fine. If you could afford to invest more money, only the sky was limiting your phantasy.

Being a cowboy always included guns. A revolver, in a holster. A toy rifle would be optional, but awesome. Those things were expensive for us children at the time when I was, perhaps, five or six years old. Over the weeks preceding carnival season, the windows of local shopkeepers selling kids toys were chock full with that sort of equipment. My eyes were glued to those windows, marveling fancy toy rifles. I also liked to go out as a “sheriff”. Meaning just adding a sheriff’s badge to my outfit. On the equipment side, toy weapons were essential. No way to go without, and if we would not be able to afford some weapon from the store, a carved and painted piece of wood would do.

During those years in the early sixties of the last century Germany’s pop culture was hugely influenced by American movies and American cultural notions. We loved movies about the “Wild West”. The cultural signs associated with the land where everyone was able to live his or her dreams, they included this notion of “law enforcement” embodied by the sheriff, against the lawlessness of the Wild West. It included weapons, and in those movies, of course, shootouts. Between the good guy and the bad guys, preferably with the good guy riding off into the sunset.

By contrast, if I would have been asked as a kid about the function of a police officer, I would have repeated the ubiquitous notion of those times which exists until today in German public consciousness: “Die Polizei, Dein Freund und Helfer”. In English: “The Police, Your Friend and Helper”. As kids, we would associate that with a friendly uniformed police officer regulating traffic, or police officers being on patrol in a car painted in police colors with a blue light on its roof, pursuing criminals on the run and arresting them.

On the “detective side of things”, or what we call “Kriminalpolizei”, it would be a bit different. If you would watch American detective movies, you would definitely see the difference to German detective movies. But one thing they had in common, whether “Made in Hollywood”, or “Made in Germany”: The detective branch was always displayed as superior to the uniformed branch. This can even be seen in the shorthand label “uniforms” for uniformed police officers: You literally reduce the person wearing the uniform to the uniform itself. That individual character is replaceable, whilst the detective guy has a distinct, mostly cool, personality. We have it in German pop culture as well, and the subtle arrogance of a detective who is expecting uniformed police officers doing the minor work for him or her, culturally they were pervasive in my childhood and long after. I think this meme runs until today to some extent. With my youngest children I love to watch “Brooklyn 99”, there you have it in a funny comedy style.

Many years later I would come across that notion of a different corporate identity again when we were attempting to conduct a fundamental policing reform in my State. Fusing both the detective branch and the uniformed police branch into a more integrated hierarchy was difficult. The feeling of being “one up” if you were to wear civilian clothes was, and is, part of the policing DNA. I can say that for Germany, but I can say that for many other countries too. This reform in my State is also part of my memories about how challenging any effort of sustainable reform of policing is when it touches what I call the DNA-level.

Back to my childhood: Next I remember in relation to police was that my father became a police officer. My father entered the uniformed police branch comparatively late. In the Germany of the sixties, a typical police career would start with police education at the age of between 16 and 18 years, followed by promotion into the lower ranks of a police officer at the age of eighteen or a little later. My father entered the police at the age of 27. I have quite some vivid memories of how this changed his life and our life as a family.

The effects of my father becoming a police officer on our family were huge. Like, he was on shift duty for the entire time between my childhood and when I left the family home. Shift duty had very bad effects on his circadian rhythm. Night shifts were a nightmare for us kids. I would come back from school at lunchtime, tip-toeing into the house, hoping I would not disrupt my father’s unstable sleep. If he would wake up too early, that would be like putting gasoline on the fire of his raging temper which he suffered from for many decades of his life.

There are memories of a police car parking in front of our house when he had an opportunity to take his lunch-break at home. Other recalls deal with with how my father struggled with letting go of a cop-attitude when being off duty. Self-righteousness, combined with power given to somebody by law, and with being prone to road-rage anyways, boy, that can lead to embarrassing situations. When my father felt that he was right and the other one was wrong, honking the horn would only be the beginning. He would pursue and try to stop the other person. Much to my mother’s despair he would rage in the car. He would get out, confront the other person, even off-duty he would file a complaint or a minor traffic citation if the subject of his rage would push back. Those were my first experiences with how power can fuel self-righteousness, and that there is a fine line between engaging in a situation where the law is violated, and how to avoid escalation.

On the other side, already as a child I saw the camaraderie that came with being a cop. His colleagues meant a lot to my father. Which is a good thing in principle. He is 87 years old at the time of this writing and he closely follows obituaries of former colleagues when they pass away. Early on I also saw glimpses of what happens if cops stand in for each other, including when there is an allegation of misconduct. My father was a law abiding person. Yet, there could be situations when he would support a minor cover-up, or justify debatable action taken by some of his colleagues. To my memory, never in a really serious situation. But who helps you in a situation when you’ve got to decide whether a cover-up is minor or not? Who are you to decide that?

There is a really fine line in this, and I would see the imminent danger many years later when I came back to the same police precinct in which my father was working. I was a detective captain assigned to a team investigating some of his colleagues who had gone rogue, from covering some knowledge about fraudulent behavior by their peers to directly and shamelessly participating in it. With no bias, the team of detectives I was part of was also checking the administrative records of my father and his colleagues. I stayed out of checking my father’s record. My colleagues who did check his records told me that my father was immaculately clean. My father was shocked about the dimension of moral corruption which had made some of his colleagues participating in a scheme defrauding the medical insurance system for own financial benefits. How could personal integrity break down to such an extent? My father wouldn’t understand.

Without an ethical compass, integrity can quickly become compromised. Then there is management, and systemic prevention through a system of checks and balances. I’ll come back to that. In my experience, any individual, even if being well motivated by ethical standards, is vulnerable to straying off-course if the system fails to protect values and to guide individuals in a practical way. Accountability is a main theme in my essays.

Not delving into childhood memories too much, I would conclude by saying that nothing in my youth and adolescence made me imagine that I would follow my father in his foot-steps. Never I had the idea of wanting to become a police officer myself. Not that I did not like the job of a police officer. I just never thought that I could possibly become one myself.

Until the age of seventeen, that is.

How I applied to become a police officer

During my high-school time I had discovered my love to science. I had a deep interest in physics, biology, and biochemistry. Throughout those years I thought more and more often about studying biochemistry and to find a job in this field of science. Until today, give or take fifty years later, scientific topics form parts of my daily reading and watching portfolio. I love learning about new discoveries. Back then, as a teenager, I ran a little chemical laboratory. A friend of mine had such a lab too. Together we would do little projects, including our own efforts investigating local environmental pollution.

Preparing for my upcoming high-school diploma all things seemed to be set for a career in science. However, one day my father suggested that I might want to consider a fall-back option. I had to apply for a slot at relevant universities offering courses in my field of interest. My father suggested to apply in parallel for a new upcoming possibility allowing me to directly enter the captain-level of ranks within the detective police branch. The police of my State was in need of officers, offering a direct entry on a medium-level of seniority for people with university-entrance qualification.

There were reasons why this proposal of my father sounded very attractive to me. On one hand, I could continue to pursue an application for studying at one of my favorite universities. Applying for an interesting job in the police was risk-free, offering the benefit of taking a twin-track approach. The other argument was that during those times Germany had a system of mandatory military service. Every male adult was meant to spend one year in the military as a conscript. Except if you would be a police officer. Police duty was duty equal to military duty. Police officer recruits were exempt from recruitment into mandatory military service.

I applied. I ran through several examinations, written, physical, and oral. I got an offer to be recruited by the Police of my State, the State of North Rhine Westphalia, in the western parts of Germany. I was offered a paid three-years police education, earning me an Undergraduate Degree in Public Administration. After which I would become a detective captain in my Police.

Next I knew, I accepted the offer. My application for studying a specific discipline in the field of biochemistry was still up and running. Three months into my police education I was granted a slot to study at a university in the same city in which I had taken up my police education. At that point I already knew that policing was my thing. With no regret at all I declined the study offer and continued with my police education.

Why did I change course? What was it that hooked me up to policing?

What had happened during these first three months within the police which made me feel that this was my path into a job career? Studying a field of science, or working as a detective, the differences are more than huge. Had I not been serious about my scientific plans? Had I become lured into the perspective of an attractive job, with a lot of power, and decently paid? Or were there first experiences within those three months that made me feel, in my heart of hearts, that this is what I was meant to do?

There are as many different sets of motivations as there are people. Over many following decades I would also see generational change in why people are choosing the profession of a police officer. Then there is the societal and cultural context which may be entirely different from country to country, from society to society, from how the work of a cop is being perceived. There are questions like economic security and financial safety involved. I can only speak for myself. Throughout many decades of my life I would have given one answer only to why I decided to stay in the police from early on: Idealism. Many years later I would also recognise that there was a second main motivation involved: The desire to achieve, and to receive external validation, the desire to be recognized.

I remember that I had early discussions with former class mates. We were a band of friends from school who maintained their connection during the initial years when we went to study at college or university, or would take up a job. When I explained my decision why to become a police officer, I said “You can contribute to change from outside, or from within.” I had decided to contribute from within.

Of course, there always is rationalization involved after having taken a decision. Whether it is about buying a specific car, or why one needs the latest IT gadget, or why I decided to stay in the police. I am aware that there often is true motivation combined with an element of convincing myself. That is how the human mind works. However, looking at 45 years of police work with hindsight, I find a lot of evidence for an idealistic character trait.

The first months

To be a bit more concrete, I need to put my police education into a context of how that looked like in practice.

I remember the first day. August 02, 1976, my father and I drove to the city of Dortmund, from my home town, Warstein. Dortmund is a big city within an even larger setup of cities forming the “Ruhrgebiet”. A sprawling cluster of cities melting into each other, following the river “Ruhr”. During the seventies of the last century these cities witnessed their first glimpses of transition from heavy coal mining, steel factories and chemical industry towards a future where coal mining was moving northbound, and steel production was slowly moving into countries offering lower production costs. Today, the “Ruhrgebiet” has transformed into a hub of service industries. Some parts have been more successful than others in this, there are impoverished parts, and flourishing parts. The “Ruhrgebiet” is going by the nickname “Kohlenpott”. A big pot of black coal, so to speak. The high landmark towers of coal mines digging deep into the ground, with elevator- and compressor-systems for getting people and machines and air supply in, and coal out, they were part of the landscape. Smoking chimneys of steel plants, the bright red light on the horizon when hot steel was poured out from blazing hot smelters. Chimneys producing a lot of heavy sulfur-smelling smoke related to chemical production. Those were the signs of a blue-collar area with workers having migrated over generations, from Eastern Europe, or from Turkey. If you’re sentimental and you remember those days back then, watch this. Today, this area carries only a few historic signs of that time, some in the form of museums. The Ruhrgebiet is very green, and often very beautiful. But some areas have also taken a depressing development. Which includes a lot of crime. Like clan-based organised crime.

Back to August 02, 1976. My father let me drive the family car. Proudly I navigated through three-lane-traffic for the first time in my life. First stop was the Police Department of Dortmund, a big conference room up on the highest levels of that tall building. There I met my future police trainee colleagues. Relatives like my father proudly in the back of the room, us new kids on the block in the first rows. Of course, some people holding speeches. I don’t remember those. What I remember is that I took an oath of office, promising to uphold the German constitution, and to adhere with the legal framework that comes with becoming a public servant in Germany. I took that oath as my first step on this path.

What I also remember: At the end of this ceremony I got two documents, and plans telling me where, when, and how to show up for the first day of police education. The two documents, though, were more interesting: The first document was a letter of appointment. Nice! The second document was an administrative note. It was telling me my official retirement date. On my first day as a public servant, in 1976, I was notified that my retirement date would be January 31, 2018!

You may have noticed that I was retired January 31, 2020. The mandatory retirement age at the time of my beginning to work as a police officer was sixty years. Only later, the law was amended and for me, the active period of being a public servant was extended to the age of 62 years.

In Germany a police officer enters a system which will allow this officer to expect, if she or he wants, to serve for an entire lifetime. It comes in steps: It is less difficult to terminate a contract of a police trainee, if performance is lower than the minimum threshold. Initial appointment is followed by a period until a person reaches a minimum time of service, earliest at the age of 27. Until then the appointment is limited in time in principle, but the reasons for termination must already be quite severe. However, at the end of that time a German police officer will be appointed for life, until the legally prescribed retirement age, that is. Termination from then on is only possible under defined circumstances, like, a more than minor criminal offense for example.

That sounds luxury, and a recipe for disaster to you? Well, no. All policing systems are different, which is a main theme in this set of essays, and I need to explain to some extent how I learned from the beginning on about the way the German system is set up, so to allow context for my specific German notion of what I call the DNA of policing.

Like a soldier, a public servant in Germany, especially a police officer, accepts with the oath of office that some privileges which are part of individual rights are being subject to important limitations. Like, I have to maintain neutrality when it comes to partisan political issues. As a member of the public administration, I have to stay neutral to party politics. I also have an obligation to behave appropriate to public expectations. Both whilst being on the job, and also to a somewhat lesser extent when being off-duty. These public expectations, or norms, of course they change over time. In the Germany of the seventies of the last century, there would have been no way to display tattoos in public, as a police officer. My arms today are sporting a few tattoos. Back then, that would have been impossible to reconcile with the public image of a police officer. Expectations would try to make sure that I honor the respect to a public official with a degree of appropriate behavior considered to be acceptable to mainstream public expectation.

The neutrality of opinion, and the restraint in voicing an opinion in public, it is part of my DNA. You can still see this today, in times of social media, or blogs and vlogs. Antagonistic speech and hate- and fear-mongering public discourse is not mine. Partly because I am deeply convinced that this is the wrong approach. But partly because an attitude avoiding bias and conduct-unbecoming sits at the heart of my socialization into what is expected from a German public official. Early 2022 I wrote an open letter on my blog reminding a former President of a Federal Intelligence Agency about his obligation coming from this legal context. You can read it here. One year later, Hans-Georg Maaßen was in the German news again. The political party he belongs to, the Christian Democrats, moved to expel him from their ranks because of alleged anti-semitic and conspiracy-ridden comments he has made on social media.

For me, ethical policing comes from an ethical attitude being a public servant, and in the German context, from an ethical understanding rooting in specific provisions enshrined in the German Constitution.

In return for giving up some of my fundamental rights when entering the police, I received an obligation, and a promise, by the German State: To care for me, which is called “Fuersorgepflicht”, or duty of care, and the promise to receive a retirement pension. So, the German system how to appoint public servants reflects a long-term relationship between the State and the individual.

I close this little excursion with an important constitutional point which I began to be taught very early on in my police education: In the German constitutional system we do explicitly treat human and citizen rights as defense rights against the State. As a public servant, I take an oath on the constitution, meaning especially those first nineteen paragraphs in which the human rights and citizen rights are enshrined, which I am obliged to protect.

As a police officer I do not protect the State exercising powers of the State. I protect the constitutional rights of citizens and other human beings. This has very profound legal consequences, and I learned about them from the first day on. Any action as a police officer with which I inflict on one of the basic rights of a citizen, whether in the form of a human right or a citizen right named in the Constitution, requires that I am authorized to do this by a specific provision in the law which is explicitly granting the authority in prescribed scenarios. In addition, I am obliged to exercise this right to inflict on other people’s life only if a legally possible action is objectively able to achieve the intended effect, and is necessary and proportional.

I emphasize this here because you will see that my service as a German police officer does, through this setup, prevent the State from using agents through which the State can do what the State wants. I am, by this legal constitutional construction, an agent of the State who is obliged to protect the rights of human beings, and only to inflict on them when there is a constitutionally compliant specific law prescribing this action, and even then, general principles may force me to abstain from exercising power, and coercive force.

I learned this early on. As a consequence I am so critical with regards to terms like “law enforcement”. We do not know a German equivalent to this term. We talk about tasks in two realms: Assisting in the identification and prosecution of crimes, and secondly assisting in preventing dangers to public security, and to a lesser extent to public order. Unlike other legal systems, there is an explicit difference between public security and public order in the German system: Public security refers to threats stemming from instances or situations which are subject to written regulations, by law or by-law. Public order refers to a set of expectations which are rooted in public values. Which can be different from region to region in Germany.

In describing why I choose to become a police officer, I will leave this here. I got these fundamentals in my police education from the first day on, and my understanding then deepened again in my senior education many years later. They made me feel that I had taken a good decision by contributing to a system of policing, without feeling like I would have become part of a control system.

I will, however, say one least thing: Throughout my junior (captain level) and my senior education (major level and up) as a police officer, I was told about the history of the German system in the Republic of Weimar, how the Nazi’s were able to hollow it out and to eradicate it, and how we set out to create a more protective version, in post-World War II-Germany. Until today, this is part of my DNA. There are several articles on my blog where I make that clear.

What happened next?

Three months turning into three years

How did I navigate through my police training after I got a first sense that this is the right profession for me?

The police headquarters were the first stop of that day early August 1976 for my father and me. The second one was at the small one-bedroom-apartment which my father had found through police colleagues in advance, and where I moved in for my first time outside the family home.

Throughout the week, a pattern of either attending class at a College for Public Administration, or alternating practical phases of traineeship in various offices of the Police Department responsible for the city of Dortmund. Fridays I would return to my hometown, gladly mingling with friends and being with my family of origin. Sunday evening would see me returning to my one-bedroom refuge, preparing for the upcoming week again. At the age of eighteen, this was my first step into the independent life of an adult. Weeks with my trainee colleagues, weekends with my former school friends, somewhat comparing notes, somewhat the fading out of a time where some of us highschool friends still managed to spend time together. It would end as we, over time, grew into relationships, marriages, family life, or wherever the winds of change threw us. But for a few years I had two home bases. Work, and weekends.

Three years of police training? Some international readers will still say “Wow!”. There are policing systems in which the police training may only last several months. There were professional experiences in my international line of work, decades later, where these different notions heavily collided. Sometimes we could manage reconciliation between these different attitudes how to train police officers. Like in Kosovo. Sometimes, like in Afghanistan, we faced some international exasperation and impatience: The German Police Project Office GPPO supported the Afghan police education into officer ranks by establishing the same mix of academic studies and practical training on the job over the course of three years. Others wanted to generate as many police officers with some most basic training.

In Germany, these three years are even only part of a larger educational effort: Police training leading to the appointment on captain level overall requires roughly three years of intense education, ending with an Undergraduate Degree in Public Administration. There are other entry forms into the police, including on sergeant level, and also some combinations allowing a shortened training for those holding sergeant level and aspiring to reach captain level. Also, if you have some specific external education in other fields, being useful in the police as well, this might count against the duration of training and education inside the police system. In any case, once on captain level, you can look back on several years of thorough police training necessary to get you there.

The same is true for additional education required if a police officer on captain level successfully qualifies for senior ranks, starting with what could be compared with “Major”, and then up to highest police ranks, comparable to what other rank systems describe as “General”. This will require two additional years of study, leading to a Masters Degree in Public Administration. We have an entire Police University for that part.

Why? May be one answer is that becoming a police officer and making it through the ranks is a life-time-investment for the State. I wrote about it earlier. Becoming a public servant is less a temporary job, except you want it this way, and more a long-term commitment. In this, the German approach falls into a category of policing systems which tend to invest into comprehensive education. In return, the system benefits from long-term and highly qualified public servants. If a policing system is interested in getting fast results, and higher transitional speed between appointment and retirement, the result may be shorter education with less depth. At least at the initial stages of a police officer’s career. The more policing is understood like a job for a limited number of years, the less a system will be willing to invest large efforts, and bigger amounts of money.

The same happens in international efforts helping to capacitate local police organisations. Mark Kroeker of the United States, one of my predecessors in my function as the U.N. Police Adviser was famous for repeating “You can not stand up a Police”. There were instances when the international community could agree on a balanced approach between getting quick capacity and the need for more time in order to ensure quality, and sustainability. In other cases, the fundamentally different viewpoints collided and struggled with reconciliation through compromise.

The result of any police education is a fully operational police officer. That officer has enormous power of decision making. She or he is entitled to limit rights of others, including through coercion including the power to apply physical force. Police officers are armed in many police organisations. From my early years on I learned that a thorough initial education will contribute to the quality of work of those of us in the police who are the youngest, the least experienced, most prone to making mistakes by not knowing it better from previous own experience. These youngest of us are forming the bedrock of work in areas where their power has the most impact on citizens: Patrolling duties, investigation duties, all this has countless effects on citizens. Improper execution can have devastative consequences.

So, I ran through three years of police training in Dortmund. Including a few own experiences giving me a glimpse on what can go wrong, why it is important to have safeguarding rails, why it is important to appreciate policing values on deep levels, and what can happen if the system of checks and balances is challenged by what my U.S. friends would call “The Thin Blue Line”, or what we have as a saying in German language: “Eine Kraehe hackt der Anderen kein Auge aus” (One crow does not hack out the eye of another crow).

There is no world with only saints and devils, there is everything in between

The way how these three years of police education were set up included segments of theoretical courses and segments of practical training. For several months I would travel to the College where I would attend courses. We learned about methods to plan and to execute police tactics and operations. There were courses on investigation methods and on forensics. I made my first experiences within the field of criminology, “the scientific study of crime as a social phenomenon, of criminals, and of penal treatment”. We were introduced into the details of criminal law, meaning the laws describing which action constitutes a specific crime. It’s sibling is the criminal procedural law, which includes the procedures which police officers have to follow in order to provide evidence, and how to treat witnesses and suspects. We learned about the other main segment of laws prescribing policing in Germany: The laws regulating public security. I learned about what the law required me to do, and what I was prevented from doing. There were study courses in psychology, in social sciences, and there also was a course about the basic law, the constitutional origin of all specific laws which form the legal framework for how a police officer in a rule of law is operating.

Alternating with such segments we would be deployed into all sorts of offices within the sprawling police department for the city of Dortmund. I found myself on patrol duty, I learned about traffic policing, I accompanied trained police officers in marked cars and made first experiences with night shift duties in unmarked vehicles. On the investigative side of things, I was progressively introduced into various activities, from day-to-day crime, like thefts or burglaries to robberies, from juvenile delinquency to gang crime, from sexual delinquency to homicide. Throughout those phases I would be part of the respective office staff and any colleague or an assigned mentor would take me into my daily tasks. Over time I would have my own first little investigative cases assigned under supervision. Progressively my work assignments became more complex and I was granted more independence in carrying out my duties.

I don’t want to give a full account here on everything that happened during these three years. What I would like to focus on are my first personal examples for specific challenges: As I got into the system, the system got into me. I had to make my own difficult experiences at the same time when I saw some of my trainee colleagues being challenged. It is easy to talk about positive experiences. I had a great many of them. It is not easy to talk about those situations where things could have gone catastrophic if the proverbial bit of luck would not have protected me, or other trainee colleagues. Luck is not part of an institutional system preventing bad things from happening. A good policing system places highest priority on proper education, mentorship, and leadership. A good system recognizes that near-catastrophic experiences are an inevitable part of life. Strong ethical-based systems strive for turning these experiences into learning, and prevent their repetition and escalation into really bad behavior. And like any system, a good policing system only reduces the likelihood of mistakes and situations “going rogue”. At the end, there are situations when one can feel pretty alone and damaged. Long and expensive education is one of the key ingredients into minimizing, and mitigating, these risks.

I’ll give examples from my training years in order to make my point.

1 – The wish to belong

For more than one and a half year we, the trainees, were unarmed. At some point then we were deemed to be qualified enough to be trained on carrying and using a police officer’s side arm. Then one day my first side arm, my very own police officers pistol, was issued to me. It was one of the most palpable moments for me where I felt that I was trusted. Pistols are lethal instruments, and they are also one of the two clear signs of power for a detective. The other one is the detective’s badge. Like, you see it in many Hollywood style movies: When a detective is reprimanded, she or he has to turn in two things: The badge and the pistol. Now I was “one of them”. I had a badge, I had a weapon. I was a cop. That was the emotional impact on me, at a time when I was nineteen years old, a bit more than a year into my police education. Until today I have a vivid memory how it felt when I walked through Dortmund’s inner city district, feeling the concealed sidearm attached to my belt. I responded to this empowerment with care. For the State, it is a huge thing to entrust a young police officer with a personal service weapon, on and off duty.

There was a trainee colleague of mine, in a later class. They had not been issued weapons yet. His desire to feel like a real detective was so strong that one day he was seen on duty with a blank-fire pistol, one of these gas pistols. The model he was carrying was looking identical to a real police service weapon of that time, a Walther PPK. Of course, his supervisor saw it. The non-lethal weapon was taken away from him. He left the police education shortly thereafter. It may sound like a little funny story. The line I take is that there is a very strong desire to belong.

2 – Witnessing the abuse of power

The desire to belong can overpower any theoretical training. Trainees crave to be seen as experienced. They will listen to the “old dogs of war” with more attention than to trainers at the academy. They will try to imitate what they see. This is good when used for learning on the job. It is inevitable. But the danger sits with the desire to blend in not only on an organizational level, but to be a peer in a social group. Like, a team of patrol officers or a team of detectives. Trainees learn to apply theoretical knowledge, and they are vulnerable to any situation when an old hand says “Oh well, forget about your training, welcome to the real world.” This can be very dangerous.

Part of police training is to learn exactly which behavior constitutes an abuse of power. Some interrogation methods are prohibited. The threat of emotional or physical violence is forbidden. Brute force and torture constitute crimes. One day, my room-mate told be about an experience of a colleague of ours: He had been assigned for duty in a unit which looked out for people with an active arrest warrant. His trainer took him to a police detention cell where he was visiting a detainee. The arrested person was uncooperative. The trainer asked “Who are you?” The person would not respond fully. So the trainer slapped the detainee in his face. This happened three or four times. The trainer assaulted, literally, an arrested person in order to make that individual cooperative. Our trainee friend and colleague stood aside. He did not engage, he did not condone, he did not walk away. He was shocked and in crisis.

If he would have reported this event to a superior, chances would have been that this would have backfired. I don’t know exactly, but I think he did not report. I on my part was asking myself what to do with this third-hand information for which there was no external supporting evidence. I did not find an answer. The assault remained undetected. I never found out how my colleague processed this situation. Did he condone? Did he justify and rationalize? Did he take it as a lesson learned about how to not police?

Was it important? Yes. 2017 a former President of the United States suggested that police can roughen up people a bit. This is simply inexcusable. I was mad when I heard Donald Trump talking like that. Because, this type of excuse will be what people hear from police officers who cross that line: They will say it is just a bit roughening up. But it is not “just a bit”. I remember this event happening to my colleague until today, way more than four decades later. This gives evidence to the moral dilemma which haunted me the very moment when I heard about it. Remember: At that time I was barely eighteen or nineteen years old. I had to decide how I look at such behavior. I had to think about what would happen if it would happen to me, if I would witness criminal behavior by a police officer. I decided to not minimize it, but to treat such behavior as unacceptable and to try to stand up for my values. I wasn’t able to file a report, though, in this hearsay situation.

There were many situations in my later life when I witnessed criminal behavior of police officers. I took the decision to apply zero tolerance, and not to be complicit. In that, these little examples above were part of my own guiding experiences. I remember my feeling helpless. I believe that some of my later managerial decisions, or my decisions when I was faced with bullying superiors, have their roots in how things happened in my early years. Again, there is this bit of luck. There also is protection through the general setup of character propensities, perhaps. But make no mistake. Relying on a protective layer of character propensities, more often than not it will not do the trick, if this is the only safeguard against crossing a line. It helps, but the real protection sits with a systemic intent to ensure ethical policing, and to invest into it, through proper education, training, mentorship, and management. Because we send young police officers out into the real world. Relying on theoretical training is not enough. It is one of the essentials when I look on efforts to reform policing.

So, back to my own path to becoming a police detective captain. In all practical segments of my education, whether on uniformed policing or on detective work, two things were crucial: My trainee colleagues and I were integrated into the daily routine of police work. Secondly there would be trainers or mentors assigned to each of us, but this system was not as comprehensive as I would recommend from my later experience. The German system has gone a long way since I made my first baby-steps into it. The role of mentorship, for example, has greatly improved. Just as one example.

Had better mentorship helped me, personally? I do believe so. Despite an already thorough effort to help us young trainees, there were many situations in which we were left to our own devices.

3 – Dopamine power and success

Waldi O. was a local hero within the police precinct which I was assigned to for three months. He was renowned for his enthusiastic engagement. He had a strong instinct when hunting down criminals. When he engaged in helping other people, he went beyond any limit. Which could get him into trouble, at times. Waldi had been a wrestler in his youth. A very compact body which had undergone years of wrestling training provided him with very strong physical power. A restless searching mind, combined with the desire to do his police job, it made him a perfect hunter. Once he was pursuing a fleeing criminal. No law allowed him to use his sidearm for shooting the individual running away. So he literally took his service weapon and threw it after the suspect, hitting him and knocking him down. Clearly a violation of any rule of engagement. Just think about what would have happened if the suspect would have been able to pick up and to use the pistol. But instead, Waldi overpowered the person. It added to his local fame for being a relentless hunter. I admired him, at the same time, knowing he had violated the rules in that situation, Waldi was one who had learned from his mistakes. He had told me that, and it was part of my learning.

One night both of us were on patrol in an unmarked police vehicle. We were called to a location where a suicidal woman had gotten to the tip of a railway bridge. She sat at the brink, her feet dangling a short distance from the electrical lines carrying powerful electrical current. We had requested to have the railway company switching off the power, but the power was still on. The woman was threatening to jump in case we would come any closer to her.

Waldi engaged in talking her through the situation. Managing to calm her a bit down, he moved into offering her a cigarette. She reached back, to us, intending to take the cigarette. Which provided Waldi with the very second he could grab her arm. As I said, Waldi was very strong. Next thing: Waldi and I jumped over the fence onto that part of the platform from which she wanted to jump. I slipped with one foot. I came close to those power lines which were still carrying high voltage in that moment. We managed to get ahold of the woman, held her, and brought her back into safety.

You have no idea what it meant for me when I realized that I had saved the first real life in my duties as a police officer. It was huge. What I say in hindsight: If I would have benefitted from a systematic mentorship, debriefing myself, my emotions, my thoughts, like on the thing with Waldi throwing his weapon, or the dangers within the life-saving operation, the impact would have greatly increased lessons learned for my professional way ahead. There was nothing wrong, since we succeeded, and saved a life. The simple question would have been: Could one do it better, next time? It is all about systematic learning.

Today, and since several decades, my police applies a very systematic way how to debrief complex tactical situations. There are specific SOP’s on that. That’s how you do it.

4 – Dopamine power and moral failure

There are situations where one will find oneself alone with disturbing experiences. The following situation I kept secret for forty years. Only ten years ago I began to be able to process the experience by talking about it to other persons.

I was assigned to shift duty in another police precinct in Dortmund. That precinct included the red-light-zone. During the seventies of the last century, Dortmund’s red-light-zone was a set of shabby blocks behind the central railway station. You’d pass dubious bars, sex cinemas, dark streets in which drunks shared space with dealers and with sex-workers illegally offering their services outside the official area designated for this work. The legal area for prostitution was the “Linienstrasse”. The city administration of Dortmund banned sex-work from public streets through a regulation which limited the legal part to this small stretch of a road. Nestled between a car park on the one side and the backside of a firefighter precinct building on the other side, one could only enter this street by passing huge metal walls which prevented anyone from looking in. Inside, small buildings formed a longer stretch, all of these buildings with red lanterns outside, illuminating big windows behind which sex workers would sit and advertise their services to potential customers.

It was part of the police duties of this precinct, of course, to patrol this street. The police placed efforts into making the life of these sex workers as safe as possible. Low-key patrolling was one of them.

Never ever in my young life I had been close to such a place. I was eighteen years old, had just finished high school. I had heard of these places. But I had never thought about going to see such a location myself. I was absolutely naive. I am not a bar-going person, never had been. Until today, my social habits do not include visiting bars where people would mingle. Except coffee bars. Dubious bars in shady districts? I had not the faintest experience. The entire thing was hearsay to me until I became a police trainee.

One night I was assigned to patrol duty with a handler of a police dog. We name service dogs K9, an acronym for “canine”. Like with Waldi O. in that other precinct, I learned about night patrolling, but in a precinct with a red-light-zone.

At one point, this officer decided to get out of the car, leaving the car and the dog at the roadside, and to take me on a foot patrol through this “Linienstrasse”. Already when entering this street with all those red lights, my heartbeat went into overdrive. Never ever in my life had I been in a situation where I would pass windows with barely dressed women offering sexual services. This was absolutely exciting. I followed this officer on his patrol through this street.

Half way through, he stopped at some windows. People seemed to know him, so he spoke to several of these women, doing small talk. And then it happened: He turned to me and said “You should make your own experiences here.” He turned to the woman and said that he would like to have her offering sex to me. For twenty German Marks.

Not only my heartbeat was in overdrive by then. My mind was fogged. I could not think any more. My brain was awash with Dopamine. I could not talk, my throat was clogged. My colleague pushed me into the building, towards the room entrance of that woman. She opened, I got in. What followed was the absolute opposite of a romantic situation. I got undressed by the woman. She nicely asked me whether I had more than 20 German Marks. I had not, so I said “no”. And I had to learn that that amount of money would earn me a hand job. I got that hand job. And what I also got was an absolutely immediate sense of immense shame after the transaction was over. I was in no state to think clearly. Shock initiated waves of Dopamine. Dopamine release was followed by humiliation. Humiliation was followed by shame. The shame included a specific form which victims of sexual abuse often experience: Because I was sexually excited when being in the room, I could not really acknowledge the true dimension of the abuse that had happened to me. How could I blame others for circumstances when I was aroused throughout the experience myself? The humiliation of being on the receiving end of a hand-job added and felt like defeat. A bottomless pit of shame and guilt, I dressed immediately and left.

When I came out, the officer gladly asked me how it was. I simply lied by saying “great”. And I never spoke about anything what had happened with this K9 handler. For the rest of the assignment to this precinct I would avoid seeing this officer. But that is only the surface of my reaction.

I did not commit a crime. Neither my colleague did. Prostitution was legally allowed in Germany, as is using the services of sex-workers. As I said, the city of Dortmund had prohibited the sex-workers from offering services outside an exactly defined geographical area, called “Linienstrasse”. What happened in that confined space was legal for any person older than 18 years.

However, from a perspective of conduct-unbecoming, the actions of this police officer pushing me into the apartment were clearly a grave violation of internal rules. If caught, this officer would have been subjected to severe disciplinary investigations. For me, a police trainee, it might have ended my future career very early on. During the late seventies, using the services of sex-workers would have raised serious questions related to my obligation to display decent behavior. Especially because I was on duty when it happened. The result was that I decided that absolute silence about this event was my best option. Ashamed anyway, this was easy to do.

This silence added to the exceptional trauma of the experience itself. The trauma is for my other book of essays. It influenced my entire life. But here, on the side of “essays on policing”, the noteworthy consequence was that I kept the silence for decades. I told not a single person about it. Until the age of fifty-five. Triggered by life-changing events I would begin to understand the role of this situation forming a tiny pearl on the necklace of a life-long series of traumatizing events.

For my police work, it hugely sensitized me about the grave dangers that come from the grey zones inside my job. It forms an essential for my own conduct-becoming, and the way how I look at mentoring and managing individuals.

It doesn’t mean this was the only near-crash I experienced. There were others to follow, after my years of education and I will use some them in later essays for specific points. In the context of receiving education and guidance through trainers and mentors this is an example for an event which will evade proper assessment. At no time I was able to really process the impact of this. Simply because I was so ashamed that I never ever spoke with anyone about it.

Today my attitude when looking back onto such experiences has changed entirely: I am very grateful that there was this little extra in the form of luck which helped me making mostly good experiences on my way inside the policing system. I am even more grateful that I could learn from mistakes. In that way, this last event helped me within my professional career to stay on course. That’s not the case for the trauma impact of it, which played out mostly in my private life only.

The majority of all learning is based on practical experiences. The responsibility of an educative system in the police sits with allowing the maximum protection. So that events from which we learn do not cause harm. Not for the trainee, and not for others.

Enough on the first three years. Taking a break. Allowing you to take a break. I will continue with reflections of the first years as a police detective, and from there with reflections on my first experiences when becoming a superviser, a senior police officer, myself. My plan is to use this solid foundation then for arguing, in another article, how these experiences formed the bedrock for my international career.