Not everything that can be faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed that is not faced.

JAMES BALDWIN

This will only be the first blog entry on this topic. I will go into the substance of how I look at this discussion in following articles. This one is intended to make clear how I look at the entire discussion, as a concerned individual and retired police officer, and a former United Nations Police Adviser. Thus, expect that my statements in subsequent articles will be as rational as I can be, and I reserve the emotional part motivating me for contributing to this discussion to this entry article. So, keep looking for follow-on to this writing, it will come soon. Expect the juice being inside a rational, but passionate debate contribution. I always try to stay away from partisan positions, except when it comes to underpinning values.

On values, I am very clearly partisan: I am United Nations hard-core, including all values on humanity represented by the UN, and developed within the UN-system. Which, by way of reminder, is the community of 193 Member States of the United Nations. We are the UN, as long as we contribute to the spirit of the UN, rather than disengaging from the UN. Like in the narrow context which will follow, engagement requires willingness to listen, rather than to yell. Any discussion which is lead in the spirit of finding consent requires to accept that it is legitimate for others to differ.

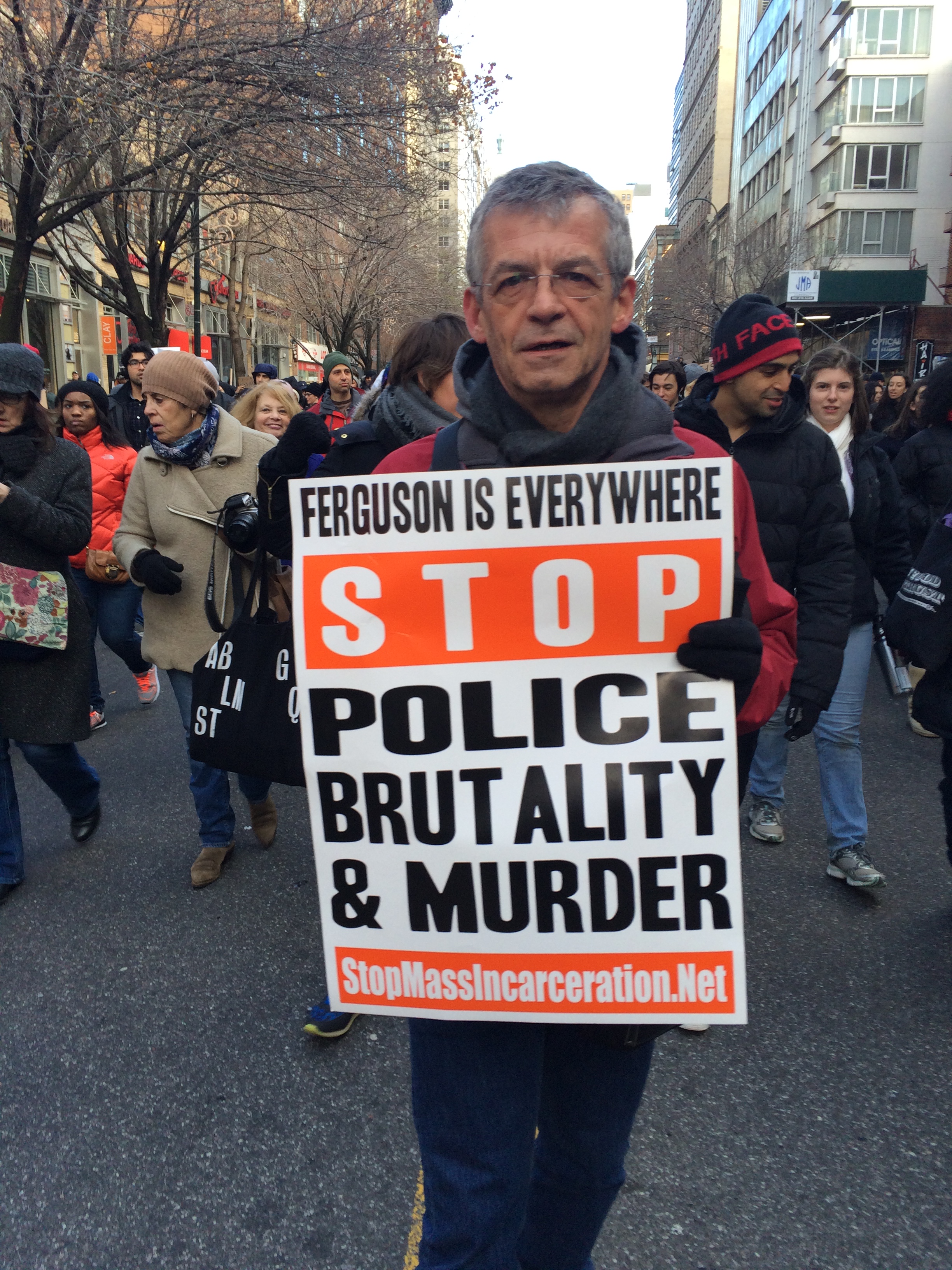

A friend of mine (who happens to be a journalist) suggested that I engage in the current discussion on policing and reforming the Police. He reminded me that, in 2014, I participated in a “Black Lives Matter” demonstration when I was living in New York (working as the UN Police Adviser). The picture is from December 13, 2014:

August 9, 2014, Michael Brown had been shot dead by a Police officer, in Ferguson. Earlier, July 17, 2014, Eric Garner died after being put into a chokehold by a Police officer, in New York City. I am singling out two out of many events that led to renewed calls for reforming policing in the United States. Both in the U.S. and internationally, brutal instances of police abuse of power, including most serious crimes, sparked outrage leading to large and peaceful demonstrations. The “Black Lives Matter” movement stems from there. As a human being, and at that time being a temporary resident in the United States, I joined my fellow American friends in their peaceful call for addressing systemic racism reflected in the Criminal Justice system, and through abuse of power through individual police officers.

Already at that time the reform discussion on policing had much deeper roots, and there is a direct line connecting the history and those days of 2014 with what happens today, 2020. However, today the outrage is amplified, and there are signs that the calls for reforming policing, and the Police, are, finally being heard. Good.

Yes, peaceful demonstrations are proving that they are one of the most essential means and an inalienable right for citizens to participate in a democratic discourse about issues that matter. And the subject matter of discussion is genuinely international: A friend of mine reported about participating in a demonstration in Berlin last weekend, with estimated 15.000 participants. It is one of many current events in Europe and elsewhere. Societies including my own German society have undertaken to conduct a self-critical discourse on the question as to which extent policing over here may also be unduly influenced by racial bias. Good.

Would all of that have happened without large-scale demonstrations? In my view, absolutely not. That is, by the way, why those who do resist these reforms, individually and institutionally, fear the demonstrations and thus attempt to label them with anything that would allow for discrediting intent of the demonstrations, manipulation of the course of the demonstrations and how they unfold, and the malicious labeling of individuals taking part in such demonstrations. These attempts are being conducted through manipulation, establishing and spreading unverified claims, false facts and lies, and using and spreading conspiracy-mongering strategies.

Most respected former U.S. public servants, including retired military officials are voicing their deepest concern about those who have adopted well-honed strategies practiced by systems and autocrats all over the World which have been criticised for exactly doing this by the very same United States of America. Good, because I hope the light can shine again, soon, and credible.

It looks like the peaceful demonstrations are here to stay. Good. Double down.

The range of topics in that discussion leading to these demonstrations is highly complex and beset with an enormous amount of emotions. It is about racial bias. It is about white supremacy. It is about countless cases of individual suffering and fear. It is about wrongful convictions, and a system of biased mass-incarceration, especially targeting communities of color. It is about the question how policing should be carried out, and how to hold police officers and other public officials accountable for their actions, including criminal actions. And much much more.

Within the current context of the United States, the contemporary development also can only be understood if put into the context of a society that is literally devouring itself, unraveled by a political partisan war ripping the fabric of consent into pieces about what is identifying and unifying all Americans, and what is so-called “un-American behavior”. It may well be that both sides blame the other for being un-American. The World is in disbelief. The ripples of instability stemming from this development have long arrived at the shores of Europe, Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. They bounce back from there, hitting the United States’s shores on the Atlantic and Pacific sides. Will that all calm down and settle into a new order, and will this be done with, or without violence?

Certainly, COVID-19 may have been a spark that set many things on fire. Fire? Not good in light of Global Warming. Oh yes, Global Warming is a fact. So, please, let us settle for consentual discussions allowing the young generations of this World to define our and their present, and their future.

These discussions need to be narrowed down. Topics have to be identified which can be taken forward, notwithstanding the complexity of the development as a whole. And in my view, it is extremely critical to take emotions out of these discussions, and to avoid antagonisation as much as possible. At the end of the day, a society needs to find an own consentual way forward in which positions converge into acceptable compromises. For, otherwise, there is no societal peace. And we do know that, without peace, there is no security. With no security, there is more heat. We can’t blame others for our own disengagement. But we always have the choice to engage. That’s why I am quoting James Baldwin.

This includes reforming policing, and the Police. After having settled on what policing is, the question how to implement it, follows second. Third then, one needs to consider how to fund what we want, and to re-allocate funding to where it is needed, and to stop funding of issues which run counter the implementation of what a society wants. So, in this third step, it is about de-funding, being part of a funding, and a reallocation-of-funding debate.

I should be clear: There is no way to establish a society with no self-policing of the rules that this society has given itself.

The violent death of George Floyd is a crime, one police officer is charged for second-degree murder and manslaughter. Three police officers are charged with aiding and abetting murder. George Floyd was subjected to police action after he was alleged to have used a counterfeit 20 USD bill for buying cigarettes. The police action ended in eight minutes and fourty-five seconds of suffering inflicted by some of the most cruel behavior I have seen in a while. And believe me, I have seen a lot.

It started with a counterfeit 20 USD bill. Why was Eric Garner being put into a chokehold, again? Proportionality of enforcement will be a point I will touch upon, later.

But I will say here that the reform discussion is triggered not by these few cases only, but because of the allegation that such behavior is systemic. That, also, makes it understandable why some try to argue that these actions are single cases. Which is not true. Truth matters, so look it up yourselves.

Another point in this first writing, attempting to look at the scope:

This picture was taken April 15, 2020, at Michigan Capitol.

This picture was taken April 15, 2020, at Michigan Capitol.

Of course I am respecting that the United States hang on to the Second Amendment. I have a personal opinion (horror and disbelief that people protest against the COVID-19 lockdown whilst carrying weapons of war), and I can also assure you that in Germany such an event would have led to as many SWAT-units as are available coming down on what would be considered a violation of strict weapons laws. But, of course, this is legal in America, thus the protest can be considered a peaceful protest.

The question I want to ask: Do you see one Afro-American person in that picture? Take a second and imagine all the individuals being black. And then, honestly, answer the question whether the indifferent action of the Police on occasion of that event would have been the same. Honestly, please!

Chances are the reaction would have been very different. That’s what I was saying in my post “Statement in Solidarity“: “Representative policing aims to ensure that the human rights of all people, without distinction of any kind such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, are protected, promoted and respected and that police personnel sufficiently reflect the community they serve.” At this moment, an overwhelming majority of U.S. citizens believes that this is not the case. Instead, we are facing a cultural form of racism, different in argument from previous forms of biological racism, but on grounds of the same attitude and thinking of white supremacy.