I finished my reading of the book “How Civil Wars Start And How To Stop Them”, written by Barbara F. Walter (Crown, 2022, Ebook ISBN 9780593137796). I wrote about it in my article “Anocracies – And Thoughts on International Efforts Related to Conflict Prevention“. There I said that I was impressed with the detailed historical account on the many civil wars, and what political science learned about their predictability. I also said that I will comment less on the second part of the book, where the author is applying those experiences on the current state of affairs in the United States of America. But here is a brief personal impression:

Purely from an emotional perspective, the first part of the book felt gripping, the second part felt like something was missing. Because the first part tells the story of not only why things went haywire, but also how they went haywire. The first part of the book talks about catastrophies that happened. Because the current situation in the U.S. is troubling, and partly deeply concerning, but has NOT led to a worst case scenario (yet?), the book is speculative in this regard, because, simply, it has to.

The author attempts to come up with a future scenario of how a descent into civil war in the U.S. could look like. When I read it, it felt incomplete. It had to. I believe the scenario had to necessarily stay away from including a potential role of individual actors which brought us to the brink of that abyss. Otherwise the book would have become speculative and politically antagonizing. The role of “Number 45” is being described in how the U.S. witnessed it’s downgrading from a starling democracy into the field of anocracies. But the book’s scenario on possible further descent stays away from involving contemporary individual actors. An that is why the scenario feels hypothetical. The absence of this link allows for concluding that we are, perhaps, far away from seeing one of the most stable democracies of the world itching closer to internal chaos. Which we are not, as I believe.

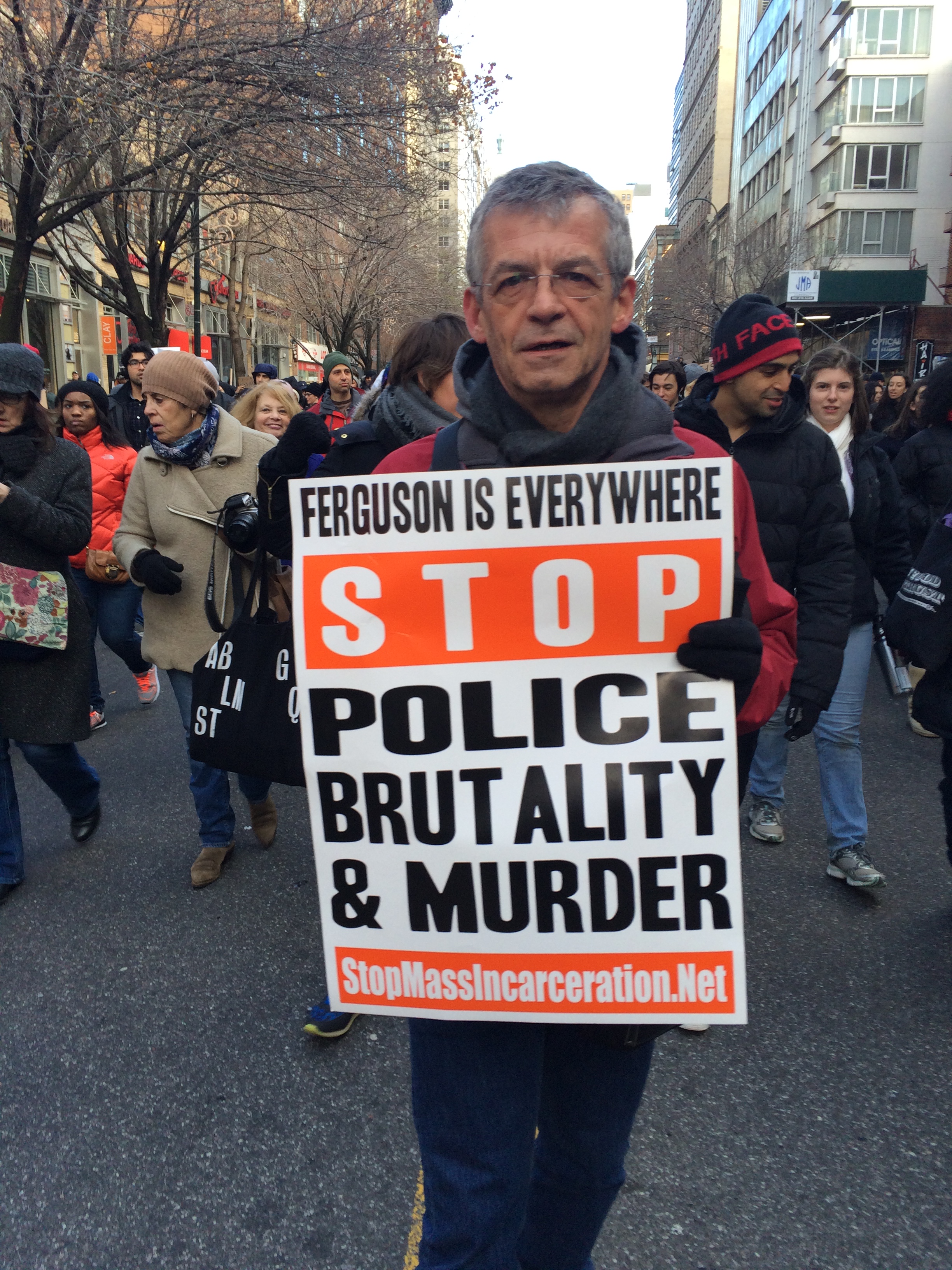

Here are two recent news articles which may make you better understand where my concerns are, still allowing me to stay out of the same trap. Make your own conclusions on whether the future may bring us closer to worst-case, just by reading and thinking about this one, and this one. We are a far cry away from being out of trouble. The mid-term elections in the U.S. are coming up, I feel we are in for a very bumpy 2022. From a European perspective, the current stabilisation of transatlantic jointness is extremely fragile, depending on future development.

At one point I was wondering what would happen if a future presidential candidate would claim his right for using Twitter back. It feels like “You’re damned if he is allowed, and you’re damned if he is not”. The claim of the far-right that it is fighting a corrupt, even pedophile global cabale, including depicting the free press as the enemy of the people, it will see a new and even more intense replication: The next round of racism, xenophobia, white supremacy, male domination, conspiracy theories challenging the efforts to fight the pandemic, and global warming, attempting to establish a narrative fighting Western democracies, it is just coming up. And the use of social media will be pivotal for those who attack, and those who defend.

The jury is out how this unfolds. And then there is the nutshell of Barbara F. Walter’s point how a fragile and unstable further descent into becoming an anocracy can be turned around. Here, the author refers to a piece of work she was commissioned with in 2014, for the World Bank. Like other scholars, the author found three factors standing out by far as being critical for preventing descent into conflict and chaos, including civil war: (1) The Rule of Law; (2) Voice and Accountability; (3) Government effectiveness. So, we will have to think about how we translate these fundamentals into concrete action allowing people all over the world to trust the form of governance which we say is the best of all alternatives we have been able to come up with so far.

So, here we are again. It is why any effort getting us collectively out of the currently very troubled waters must look at the rule of law, which Walter describes as “the equal and impartial application of legal procedure”. I stick to the definition of the rule of law as adopted by the United Nations: “For the United Nations (UN) system, the rule of law is a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of the law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness, and procedural and legal transparency.“

However, my experience entails that in order to establish any rule of law, there needs to be a large consent of the respective society in how this principle is applied, and this consent must go beyond any larger factionalisation in that society. Any large faction of a society must accept this larger principle, rather than challenging the application of a rule of law as being biased, being imposed on them by other factions. Those who stir conflict for advancing their own objectives, they always will establish a narrative that there is no justice for their constituency. They will portray the rule of law as being a weapon wielded by their enemies against them. What these individuals do is to undermine the trust of their followers in a rule of law applied to their society as a whole. Which points to a second invisible feature of any successful establishing a rule of law: Trust.

It is about trust accepting the specific rule of law, for myself, and others, for the powerful and the less powerful. And it is about trusting that justice will always attempt to prevail, no matter how long it takes. Because very often, it can take a long time. And still, after many years, cases may be unresolved, often are. A society at large must trust the course which justice takes, even if individual members experience pain because their grievances are open and festering wounds for many years, before closure is possible, or sometimes even never.

For me, this challenge can be seen nowhere else with all clarity than in situations where I contributed to the efforts to re-establish a rule of law in a society where it had broken down. May be I will write more about a few of those experiences. Here it would be too long, because I want to finally focus again on the critical role of social media. Here is just one example:

There were two main ethnic factions in Kosovo before and after the violence ending in 1999. Under the UN Security Council Resolution 1244 Kosovo found herself with a majority and a minority faction, no form of own governance at all, and no rule of law beyond what UNSCR 1244 tasked us with. The Old had broken down and had to disengage. The New was not there. It was to be established, and being part of the international community engaging in assisting in finding a new New, I was representing the international interim police.

Whilst, on a technical level of developing policing, and helping a new Kosovo Police to emerge, being more and more successful, we found ourselves in a classical “Catch-22-situation”: All factions involved were blaming us not being able to provide security, and justice. Each side would accuse us to act on the interest of the other side’s agenda. And practically it meant that in case of any evidence of a severe crime which would allow us to make arrests, and prosecute suspects of grievious crime, there would not be a societal consent, or trust beyond factions. At least at the beginning. During those early years, any action by us leading to an arrest would be perceived by one faction as a biased, if not politically motivated, action in favor of the other faction. I have many examples for both factions.

I believe that, over time, some trust could be instilled. Not only that the Kosovan society at large moved forward towards healing from own wounds. Not only that our persistent sticking to a common rule of law for All slowly helped in setting some foundations for trust. Not only that the real success story is the work on the credibility of the Kosovo Police itself, establishing itself as a trusted actor within an emerging rule of law. But any development until today also shows how fragile this trust is. Including in recent times, operational situations can demonstrate how quickly old tensions, mistrust, and biased interpretation of events can break up. But what I want to demonstrate here is exactly that: That any rule of law is critical for peace&security in a society, and that this does go way beyond the technical application of such a principle.

It requires acceptance of that rule of law by a majority of all constituencies in a society, and it requires a sound trust in the equal application and adjucation of that rule of law, beyond personal grievances, and existing factions.

As said earlier (in my first blog article on this book), this holds true both for a society moving towards a rule of law, and it applies to a society where the efforts of trusting a rule of law are heavily undermined by the spreading of misinformation and fake news. Whether the society moves into a positive direction or a negative direction, it is the middle zone between the Old and the New which makes the situation most volatile.

All three factors mentioned by Barbara F. Walter, (1) The Rule of Law; (2) Voice and Accountability; (3) Government effectiveness played into any descent into chaos I have personally witnessed.

In 2022, the means to disrupt by using manipulative voice and amplifying non-accountability are a global challenge: Social media has become a bull-horn for those who know how to exploit fragility, and to further it.

So, how to translate Barbara F. Walter’s message, that civil wars can be avoided, into practice?

By taking responsibility for own action, and making our voices of reason being heard, day by day. Neil Young requested from Spotify to remove his music from the platform because Spotify is hosting “The Joe Rogan Experience”. Neil Young did not want to be on a platform which prominently features a protagonist for this type of spreading misinformation, lies, and manipulation, including wildest conspiracy theories about some mass-hypnosis being used by a global cabale enslaving citizens. Joni Mitchell followed suit, and she is not the only one.

This fight is taking us on a long haul, it is far from being over. Every personal contribution matters.

This picture was taken April 15, 2020, at Michigan

This picture was taken April 15, 2020, at Michigan